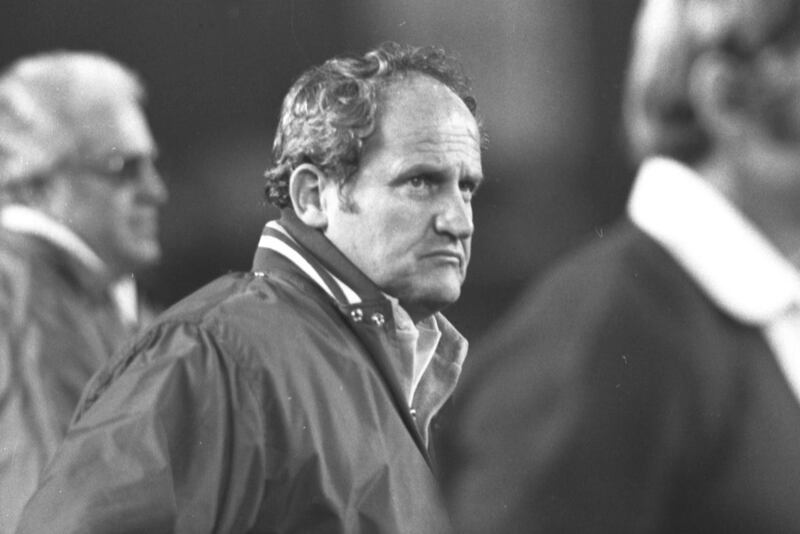

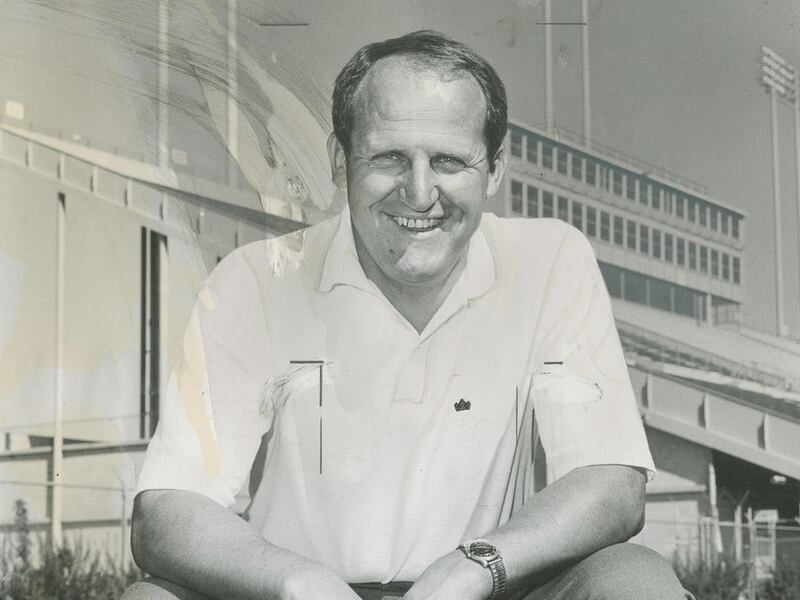

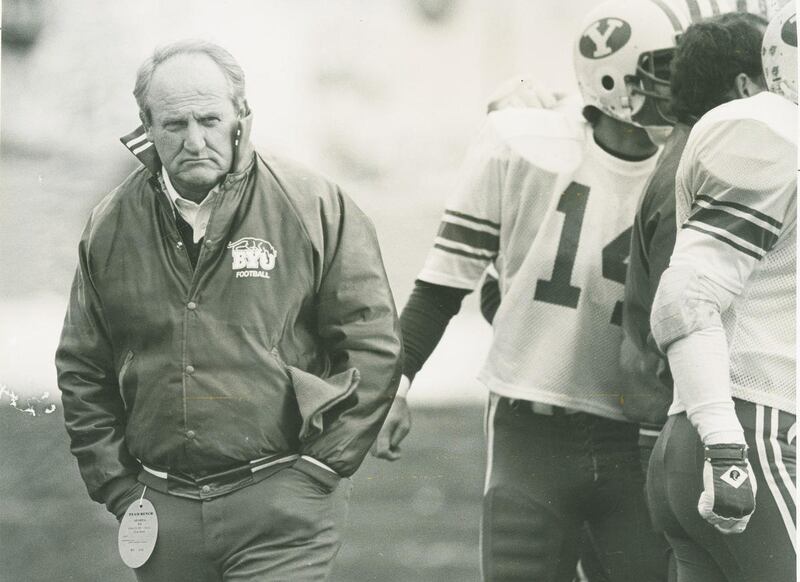

LaVell Edwards’ legacy will forever be the feat of creating an iconic football brand from something that had always been so much less. He was a man known for his remarkable insight into the souls of young men. An innovator and visionary, he made friends as easily as the rest of us breathe. He will be remembered as a tremendous example, a pillar among his peers.

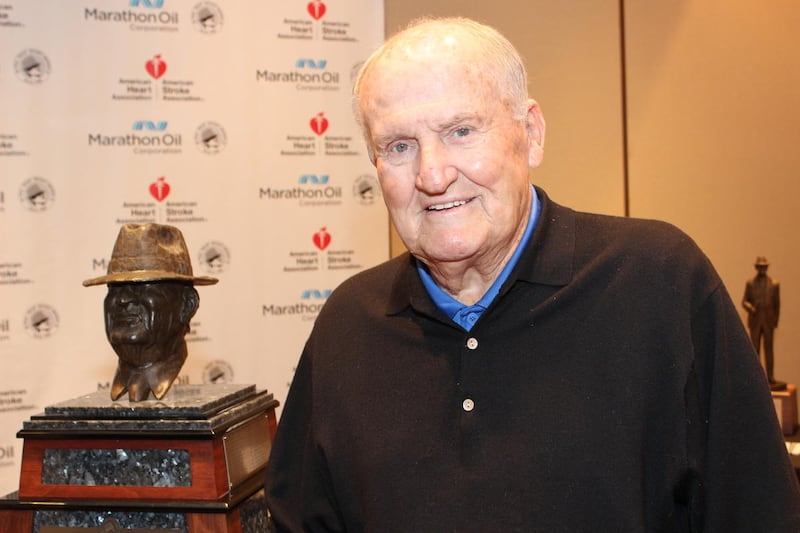

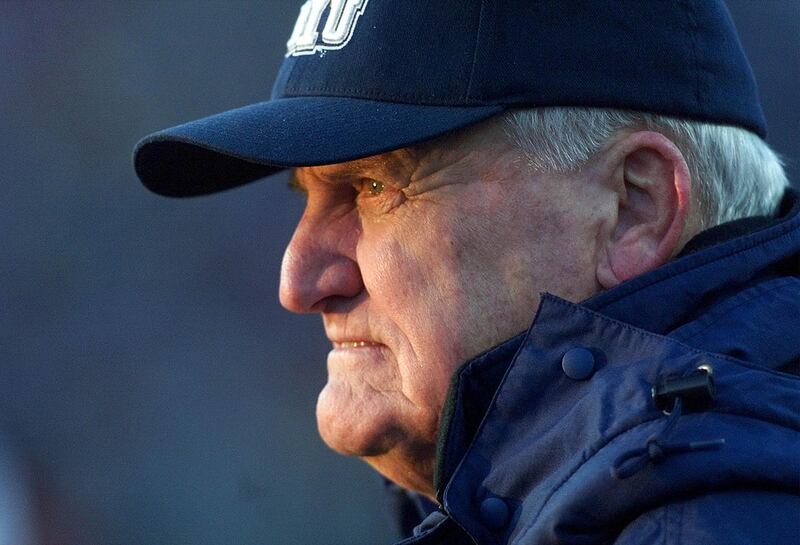

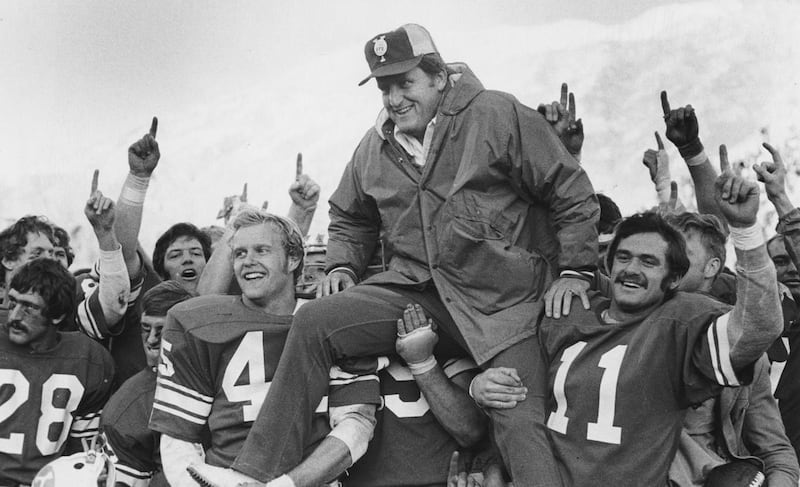

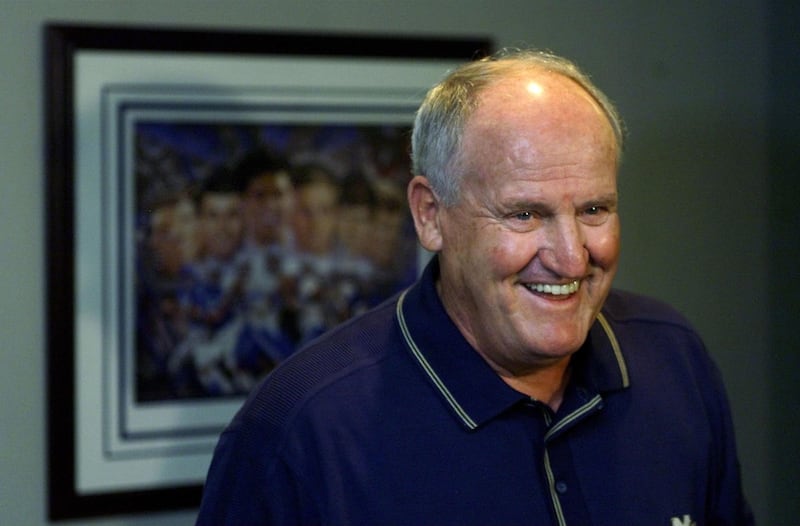

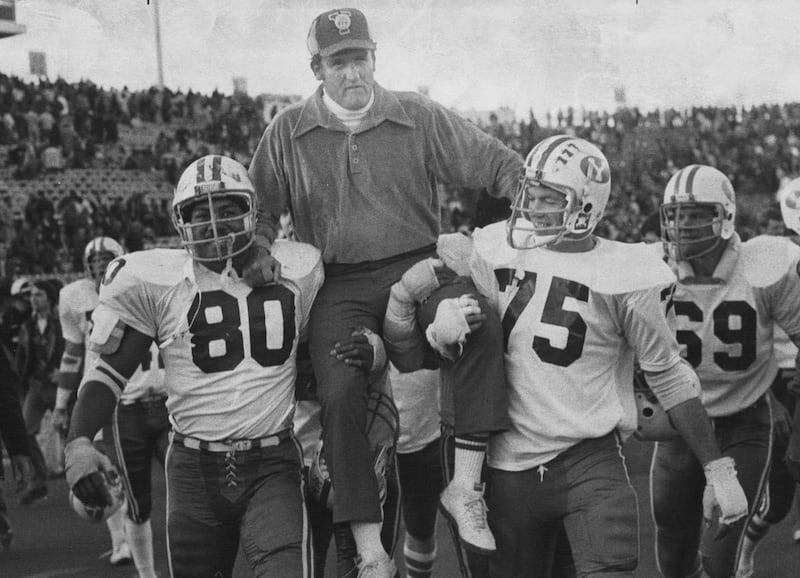

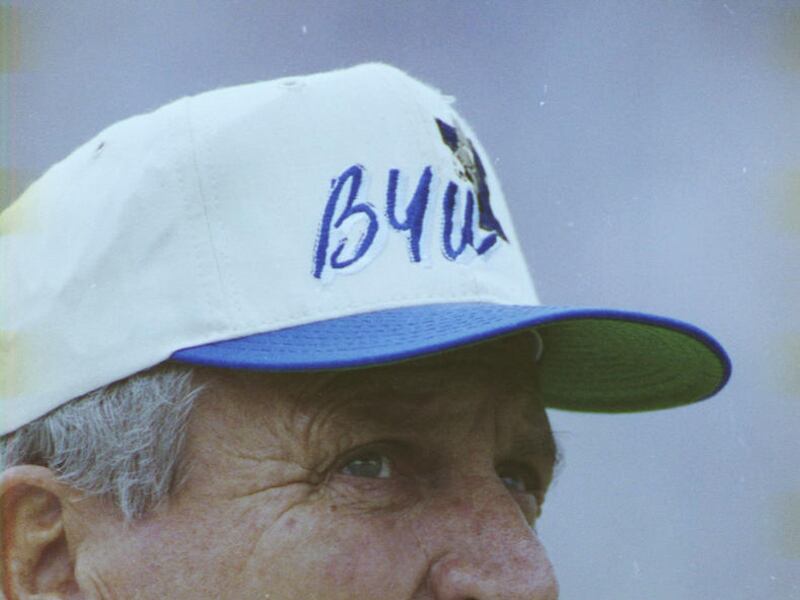

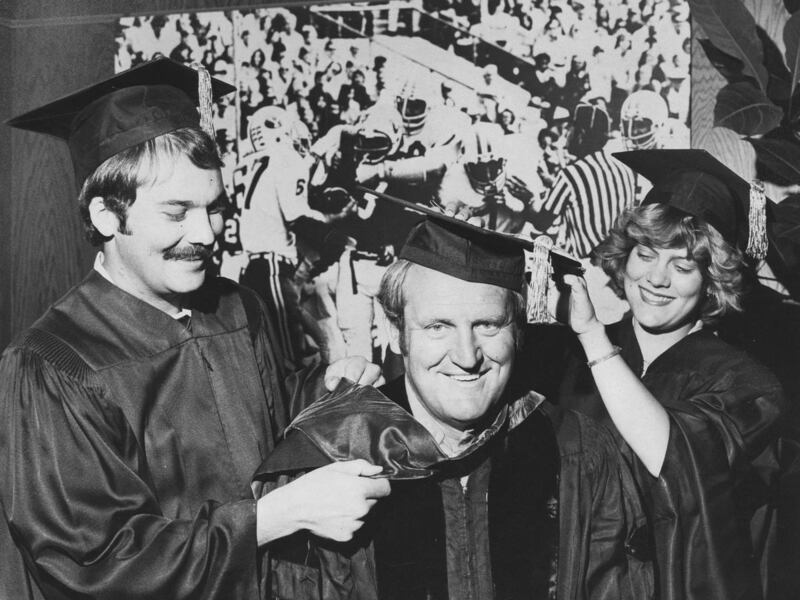

Edwards, the head football coach at BYU from 1972 to 2000 who led the Cougars to the college football national championship in 1984, died Thursday, Dec. 29. He was 86.

TIMELINE: Important dates in LaVell Edwards' history.

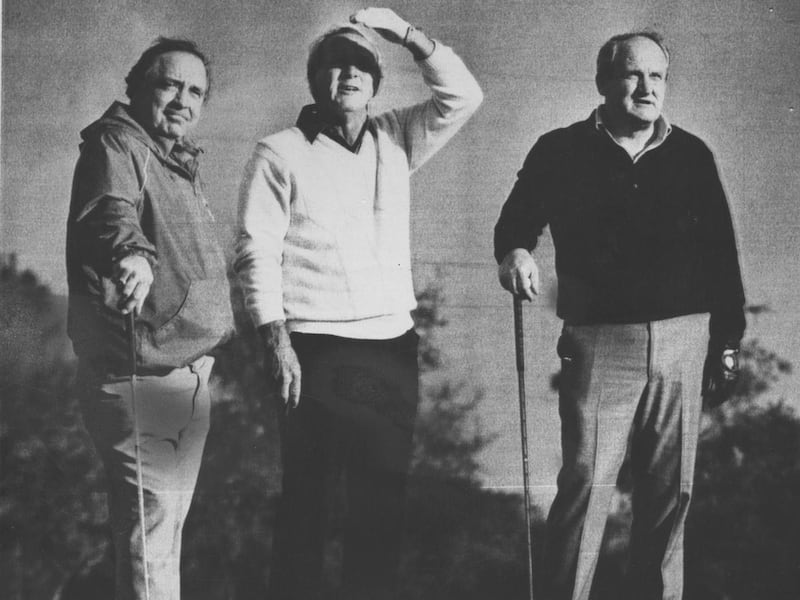

Edwards fell several times inside his home this past week, according to friends. His health rapidly declined following those incidents. On Christmas Eve, Edwards fell and broke his hip. He was attended to by his son John, an Ogden orthopedic surgeon, right before his death. According to former player Jeff Blanc, a running back in the '70s, Edwards had planned to meet him in St. George for golf before BYU's bowl game in San Diego. "He said his feet were hurting him and he couldn't make it. But he could still shoot his age on the golf course."

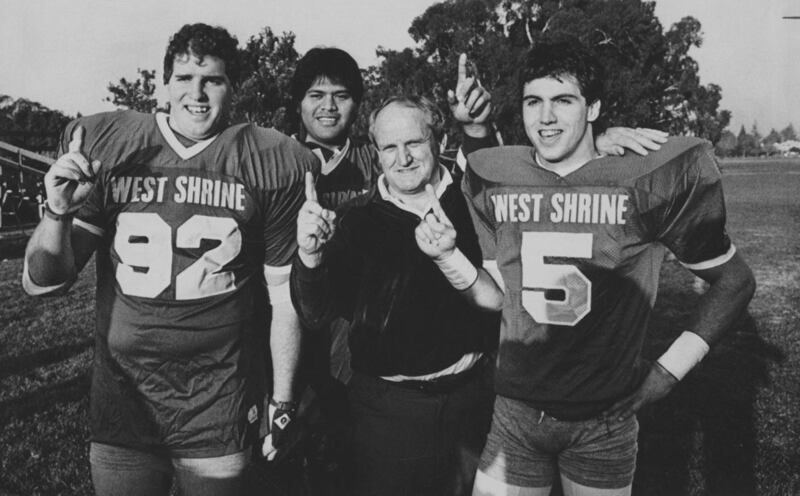

He was a man who players, family and friends remember with unfettered adoration. The tales told of his life and times bring both smiles and tears. His victories are part of college football lore, and the heroes he ushered into football sainthood in Provo are legion.

Edwards’ style inspired a generation of coaches, including Utah’s Kyle Whittingham, BYU’s Kalani Sitake and Washington State’s Mike Leach, and he was an early model for the NFL’s Andy Reid, Mike Holmgren and Brian Billick.

Edwards was a megastar at making and retaining relationships, an art he excelled at throughout his life.

Edwards was born Oct. 11, 1930, to Philo and Addie Edwards and spent most of his life in Utah County.

His parents owned 80 acres in Buckhorn, Utah, but decided to move one summer before his birth. They couldn’t sell, trade or give the land away until someone agreed to pay Philo $10 an acre. He took the $800 and put a down payment on a 17-acre orchard in Orem.

Being from a big family didn’t exempt LaVell from chores. He learned to work hard, often milking cows and picking fruit. His parents said they never heard him swear, and he was a dependable son.

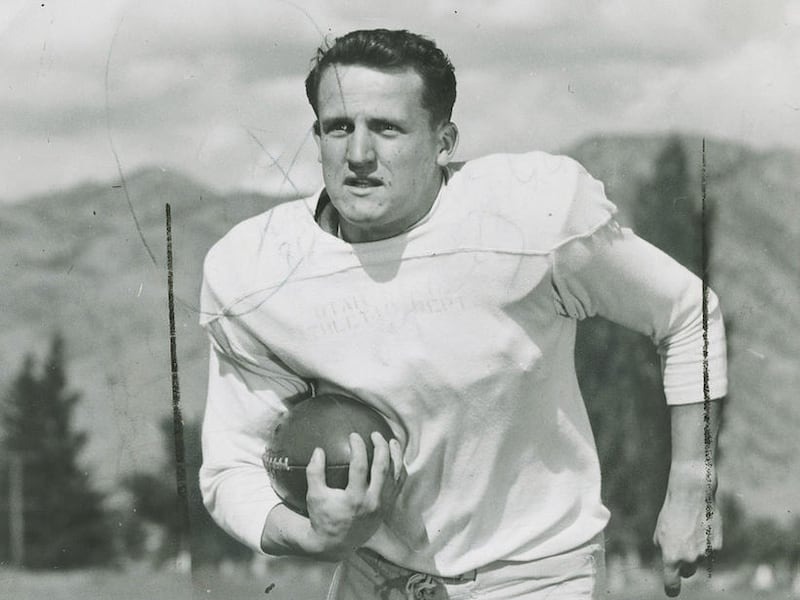

Edwards graduated from Lincoln High in Orem before attending Utah State University.

In Logan, Edwards became a football star. He played linebacker and center and was soon named team captain. He was an all-conference lineman before serving a two-year commitment in the Army. “He wasn’t elected. It wasn’t a democracy under coach (John) Roning. But LaVell was a leader,” said teammate De Van Robbins, a San Francisco dentist.

It was in Logan he met Patti Covey from Wyoming, who would become his wife and lifelong sweetheart. He and Patti have three children, Ann (Cannon), John and Jim.

LaVell and Patti once accepted an invitation from their friend Sy Kimball to go fishing in Alaska.

Edwards liked to fish, but it wasn’t as big of deal to him as it was to Kimball, a veteran of numerous deep-sea fishing trips off Baja, California, and the owner of a giant yacht. Kimball wanted the trip to be a special experience for his buddy, the coach.

The first morning, Kimball waited for Edwards to arise, and finally had to wake him up. Not exactly raring to go, LaVell would have slumbered through the entire outing.

Once onboard and out on the water, everyone was outfitted with tackle, poles and gear, but the salmon weren’t biting. After a long wait, Kimball noticed LaVell’s pole wiggling. He nudged the coach and asked him to test the line. Sure enough, Edwards had a lunker.

Kimball tells this story with a laugh because LaVell Edwards is a man who is so easily loved and such a magnet for success — just like the way that big fish came calling for the guy who was barely interested.

That’s the type of banter that follows Edwards, who in his own part of the world (and a few others) is a legend.

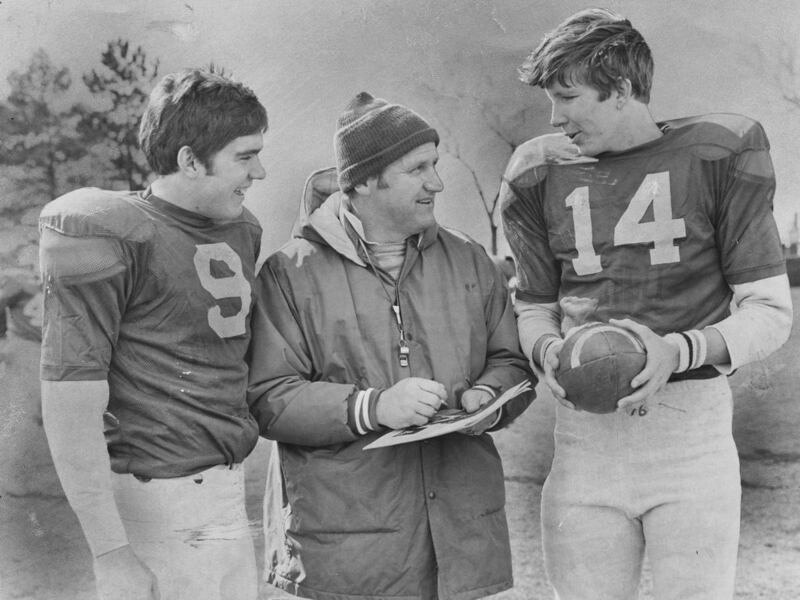

Former BYU quarterback, San Francisco 49er and Super Bowl MVP Steve Young is a legend in his own right. The current ESPN commentator likes sharing the story of his recruiting trip to BYU the first decade of Edwards' coaching career. He remembers sitting in a line of guys outside Edwards’ office who were waiting to see the head coach. He was the last guy.

“LaVell knew my name but not much else," Young recalled. "I didn’t know if he was going to offer me a scholarship or not. In his office he was sitting in his chair, and I saw a bunch of spiritual books on the shelves behind him.

“A coach with spiritual books. I was pretty impressed. I didn’t think the two could mix," Young continued. "As I sat there, I thought for a second he had fallen asleep. He started chewing on his tongue, like he was looking for inspiration. Then he said, ‘I think we’ll give you a scholarship.’ I’m grateful he gave me, an option quarterback, a chance. He sees more in you than you can see in yourself. That is the greatest compliment you can give a coach."

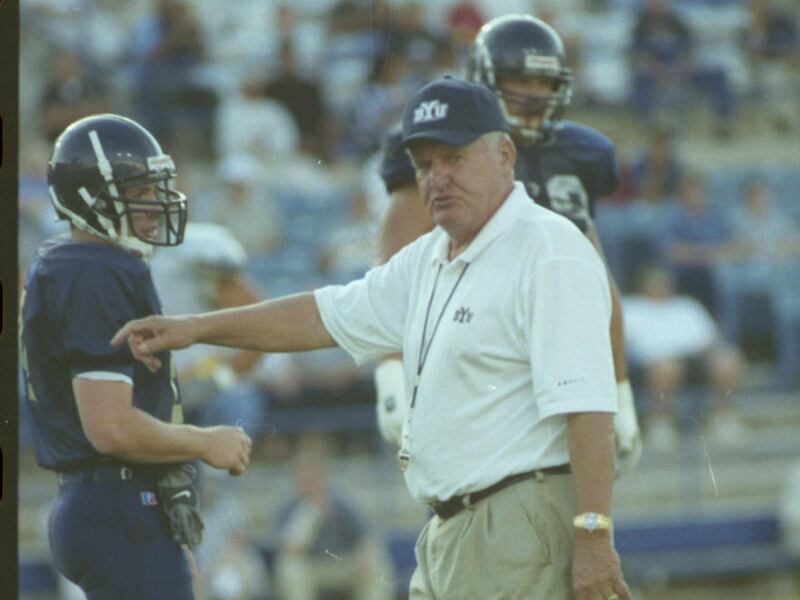

“He is like a father to the players,” said Steve Sarkisian in 1996, a player who quarterbacked Edwards’ 1996 team to a 14-1 record. “He really cares about us individually, and while he’s low key and sometimes looks like he’s bored in games, nobody wants to win more than he does. He has a fire inside of him and he loves the game.”

After 29 seasons and 257 wins at BYU when he retired, Edwards ranked as the sixth all-time winningest coach. His peers in this regard included the top echelon of all college coaches, including Bo Schembechler, Tom Osborne, Woody Hayes, Bobby Bowden, Joe Paterno, Amos Alonzo Stagg, Pop Warner and Bear Bryant.

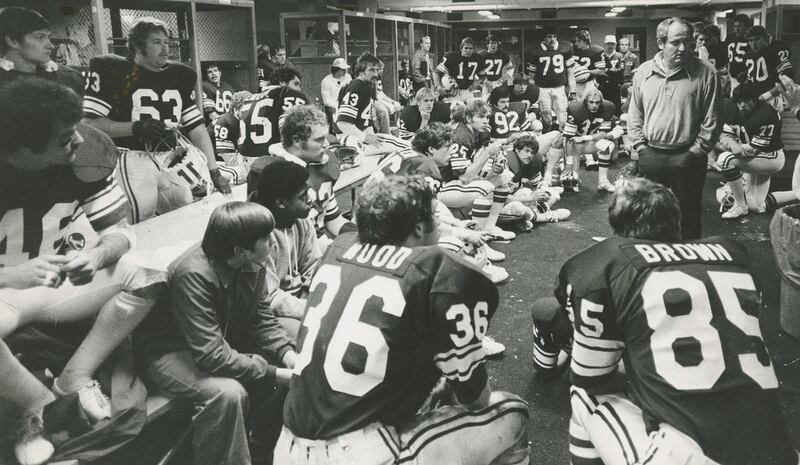

When hired at BYU, the Cougars had won just 173 games the previous 49 years, with just one conference championship and no bowl invitations. By his retirement, BYU had 22 bowl appearances and 20 league titles. His teams passed for 57 miles in his 29 seasons.

“LaVell’s consistency from one year to another has been incredible and unbelievable,” said former University of Utah coach Ron McBride, who became lifelong friends with Edwards despite a rivalry that has been heated and called toxic by some.

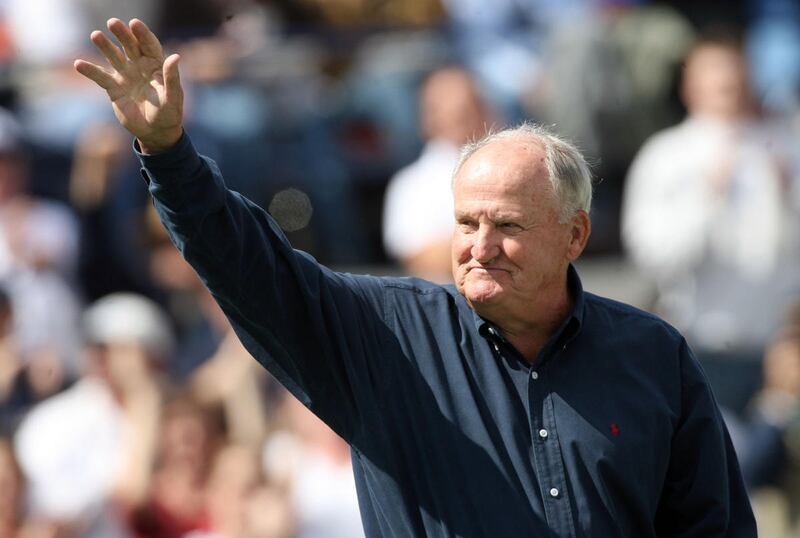

Edwards’ final game at BYU took place on a November night in 2000 at Rice-Eccles Stadium, a game in which his 6-6 Cougars battled for their lives and saw Utah outscore them 17-0 in the fourth quarter to take what looked like a final lead. A controversial no-call on what some say was a fumble by a BYU running back led to a last-gasp chance to finish a late scoring drive and send Edwards out a winner. A series of unbelievable pass plays from quarterback Brandon Doman to Jonathan Pittman extended that drive and brought the Cougars inside Utah’s 4-yard line where Doman dove over the goal line for the winning TD in the closing seconds.

“It was almost like a miracle,” said Pittman. “Somebody was looking down on us. Somebody wanted us to get him (LaVell) that victory.”

From the time he took over at BYU in 1972 through the 1985 season, Edwards’ teams won 122 games while losing just 36. From 1979 through ’85, the Cougars were 77-12 and won seven consecutive conference championships. Over two-and-a-half decades, 10 of his players were consensus All-Americans. He also coached seven Sammy Baugh Trophy winners, five Davey O’Brien award-winning quarterbacks, a Heisman Trophy recipient and two Outland Trophy winners. He saw one of his former players on the NFL’s Super Bowl championship team every year from 1980 to 1992.

Six of Edwards’ players, Ty Detmer, Gordon Hudson, Steve Young, Jim McMahon, Marc Wilson and Gifford Nielsen, have been inducted with him into the College Football Hall of Fame, now located in Atlanta.

Edwards never held a job outside the state of Utah. His first coaching job was at Granite High, where he coached eight seasons without a winning record. Hal Mitchell hired Edwards as an assistant coach at BYU in the mid-1960s because, as Edwards tells it, he was the only Mormon who knew how to run the single wing. Oklahoman Tommy Hudspeth replaced Mitchell in the mid-1960s, and in 1972 BYU asked Edwards to take over the program. By his own admission, he had no groundbreaking ideas and he wasn’t a dreamer looking for a throne or pot of gold.

Edwards had some ideas. He thought he could take some weaknesses in BYU’s athletic stock and turn them into positives. He also believed in loyalty, friendship and the potential of young men. He believed if he hired a coach, he’d let them do their job. He was the first BYU head coach to see missionary service as a potential advantage instead of a stumbling block.

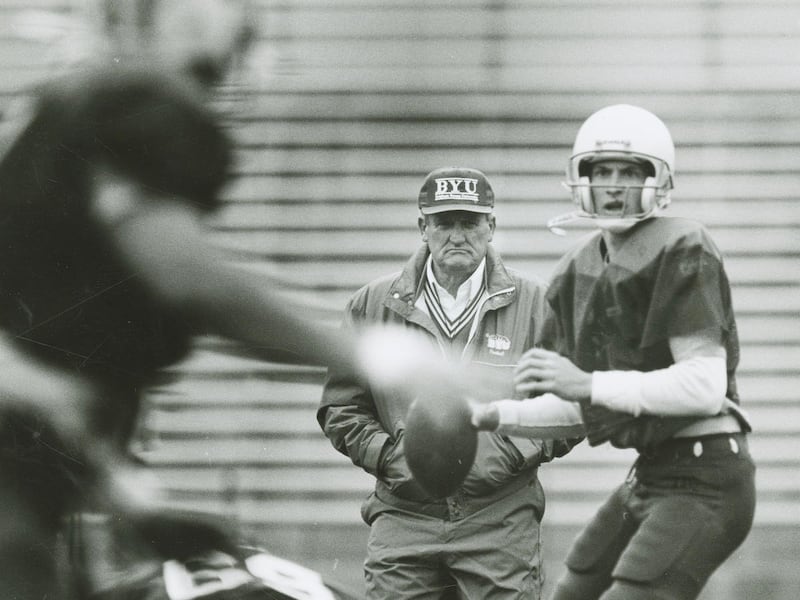

In time, Edwards became the winningest coach in the western United States and revolutionized the college passing game. “We got lucky with the pass because people weren’t used to seeing what we did,” he said after retirement a few years before his death. In his heyday, five of the top 11 single-season passing efficiency performances in NCAA history belonged to BYU quarterbacks in Edwards’ system. Two were by Detmer and one each by Sarkisian, McMahon and Young.

Edwards’ teams led the nation in passing offense eight times, led the nation in total offense five times, and led the country in scoring offense three times.

One of Edwards’ first hires in 1972 was a former Tennessee quarterback named Dewey Warren, who helped install a passing philosophy to put defenses on alert. But, ironically that year, his running back Pete Van Valkenburg ended up winning the NCAA rushing title.

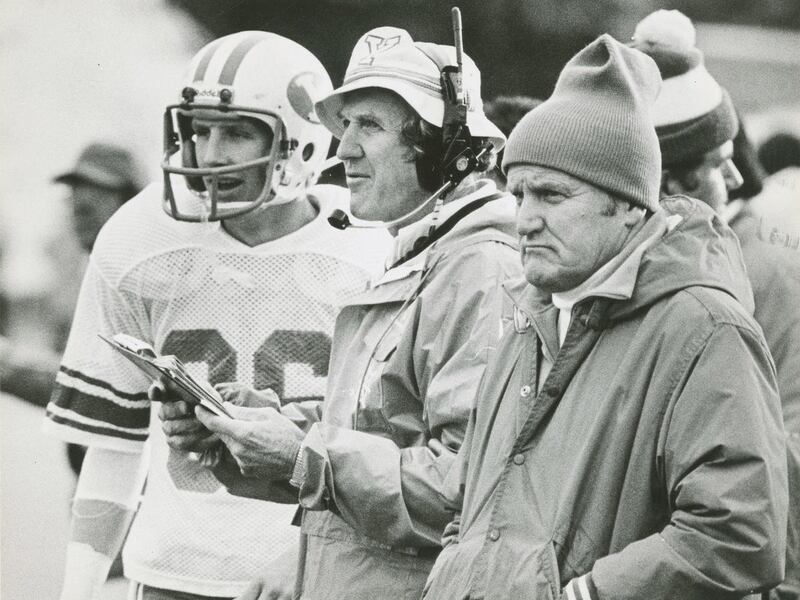

As Edwards continued to tweak his idea of using the pass in the 1970s, he hired Doug Scovil, who had worked with the famed Sid Luckman out of California, and a graduate assistant named Norm Chow. Later he added Mike Holmgren and then Ted Tollner — all of whom joined Chow in developing what became BYU’s famed air attack. It all took off with a junior-college transfer quarterback named Gary Sheide, who, in 1974, led the Cougars to their first-ever bowl appearance, the Fiesta Bowl, against Oklahoma State.

Edwards’ roots were right in BYU’s backyard. His parents, Philo and Addie, were salt of the earth, God-fearing, simple people who taught basic principles of honesty, charity and ethics.

In 1984, Philo Edwards stood up on his old legs before his church congregation and bore a witness of God before his neighbors — thanking his maker and expressing love for his petite wife Addie, then 87, for his full life and his 14 children. Included among those was No. 8, the celebrated LaVell.

A big, handsome, athletic looking man, Philo told church members he had experienced so much in his life to be thankful for. And there were things he hoped to still do in his life. Asked by a neighbor afterward what exactly he’d like to see before he died, he said, “I’d like to see my boy win a national championship,” he replied.

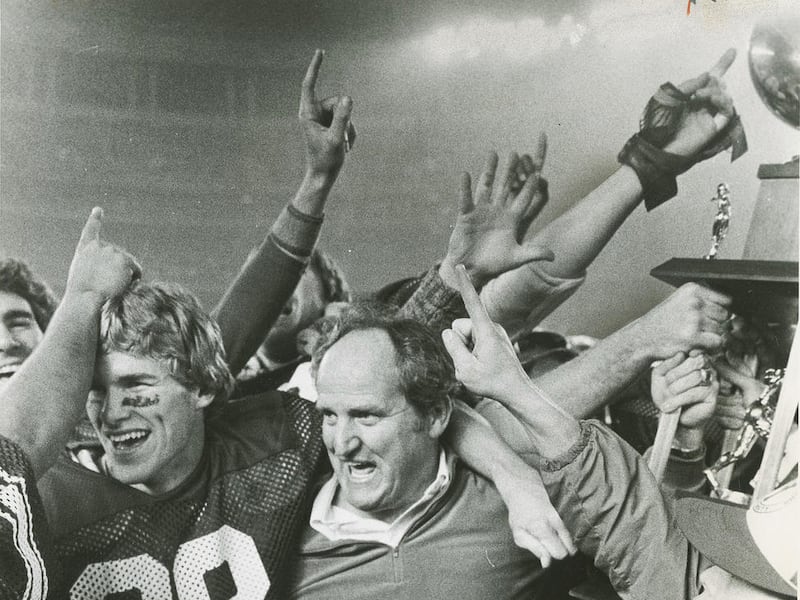

In a few months, Philo’s wish came true. In the 1984 season, national contenders Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Washington lost games and undefeated BYU climbed to No. 1 in the polls. When none of the contenders would break their respective league’s bowl ties to face BYU, the Robbie Bosco-led Cougars played and defeated a 6-6 Michigan team in the Holiday Bowl. Afterward, AP and UPI voters unanimously crowned the Cougars national champions.

That feat triggered a political movement among power legacy football programs across the country, and it led to the creation of the Bowl Coalition, the BCS, congressional hearings about anti-trust claims, and then the College Football Playoffs we have today. “Never again” was the talk in the back room of the nation’s major conferences. “Never again” would a program outside of the blue bloods rise to that lofty rung. And that charge has held true politically as the NCAA has evolved since 1984.

“Everyone out there knows what LaVell’s accomplished,” said former Syracuse coach Dick McPherson in 1984. “He’s done the impossible.”

“He is one of the most honest men I’ve known” said Grant Teaff, former Baylor head coach and athletic director. “And you can’t separate the coaching from the man.”

Edwards knew the life of a fruit farmer. He sold shoes in a Salt Lake City Sears store, worked for city recreation departments, and taught physical education at the high school and college levels.

“It’s hard to imagine him not being a football coach,” said Robbins, his former teammate, in an interview in the mid-1990s. “He always wanted to be one. He never had any other aspirations that I know of.”

The late Penn State coach Joe Paterno called Edwards one of the “true giants in our game,” and praised his integrity. “He is a magnificent human being and has done a fantastic coaching job. We have had some great games. We beat them up here, and they kicked our ears out there. When you played him, you played against a man in the program that had a lot of class.”

The late Dick Felt, once a defensive back at Lehi High, went on to play at BYU and the NFL before working as an assistant coach for Edwards for more than two decades. Felt remembered Edwards as the same guy he knew in high school and college as a rival player, then as his boss and lifelong friend.

“The way he handles young men is outstanding,” said Felt. “He’s honest and patient with players, and genuinely likes these young men. He teaches that there’s more to life than football and that, in my opinion, separates him from other college coaches.

Trevor Matich, an ESPN sportscaster and former center on BYU's 1984 national title team called Edwards a father figure.

"LaVell loved his players like a father loves his children," said Matich. "You felt that. And you didn’t even realize how much it mattered at the time. The wins, the trophies and championships are important because it’s hard to win at such a hard level with so much consistency like LaVell did. You look back now and you realize how much LaVell helped you to grow up in the right way. That, to me, is his real legacy.

“His players respect him," Matich continued. "You see that after years and years when they return. You don’t acquire that respect just by being a coach. You have to earn it.”

Two of the living BYU presidents who presided over the LaVell Edwards era are on record with their praise. Both are members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“When we named Coach Edwards to be the new head football coach at BYU in 1972, we knew that he was the popular choice of the players,” said Elder Dallin H. Oaks in a statement at the time of Edwards' retirement.

“We knew he was a sound tactician. He knew the game. … He also believed in the mission of Brigham Young University. He believed right off the bat that returned missionaries could play football. Before LaVell, we had no more than two or three returned missionaries on the team.

“After a couple of years under Coach Edwards, those numbers shot up significantly. That was a good thing for the university and the team. He was way ahead of his time in that vision and in many others. LaVell’s success as a football coach has given pride to the university community. But, more importantly, his success as a leader, mentor and role model has blessed the lives of thousands of young men and women and their families.”

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland echoed those sentiments.

“Coach Edwards was always an example of what you would want your football players to observe, then emulate,” said Elder Holland. “One of LaVell’s many admirable characteristics is his constancy, his stability. If we won, he was happy, but his delight was always modest. And if we lost, life was still good because he had Patti and his children, he had his players, and he had his faith.”

Edwards’ official record as a college coach was 257-101-3. His quarterbacks threw over 11,000 passes for more than 100,000 yards and 635 touchdowns. He took BYU football to where many said it could never go.

But if you ask those who knew him, he was always about so much more.

Funeral plans are pending and will be announced soon. A family friend said a public funeral will be followed by a family funeral. In lieu of flowers, the family asks contributions be directed to the Utah County Boys and Girls Club. For more information go to bgcutah.org.