SALT LAKE CITY — Two weeks before this year’s legislative session, Greg Hughes was in his office on Capitol Hill, carrying himself like a king holding court.

As usual, the Utah speaker of the House was impeccably dressed, wearing one of his shirts monogrammed with his self-given nickname: LB — "Lucky Bastard."

Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes, R-Utah, at the Capitol in Salt Lake City on Jan. 14, 2017. | Jeffrey D. Allred, Deseret News

The speaker, 47, was amped, his blue eyes flashing, his dimples working overtime as he talked in his rapid-fire cadence, first to representatives from the beleaguered Utah Transit Authority, then to a sophomore legislator from Hooper, and finally to a couple of reporters trying to suss out the agenda of the man who many say is the most powerful political figure in Utah.

As Hughes got going, he rose from his chair and acted out a fistfight he’d gotten into decades before in his native Pittsburgh. His chief of staff, a former lobbyist named Greg Hartley, groaned as Hughes pantomimed the fight.

“He has my arms, like I’m on the ground,” Hughes said, in his slightly high and reedy voice. “And he has my arms under his knees, and he is just boom, boom, boom, boom. And he said, ‘Do you give up?’ And I would take the blood in my mouth and I would spit it in his face.”

Hughes laughed in delight. But Hartley seemed worried about the optics, and half-jokingly reminded Hughes reporters were in the room. For years, they’d been trying to soften Hughes’ image as a volatile legislator who would yell at political foes until the veins in his neck were bulging.

Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes is joined by former speakers of the House during a rally for GOP presidential candidate Donald J. Trump in Salt Lake City on Nov. 1, 2016. | Scott G Winterton, Deseret News

But Hughes didn’t care. It had been a good few months. He’d been in discussions with President Donald Trump’s transition team about a Cabinet spot, possibly as transportation secretary. And although that position never materialized, he still talked to high-level people in the administration, including Donald Trump Jr.

“After we won, I wondered if we’d still text,” Hughes said. To his surprise, they did, and on New Year’s Eve, the two even had a discussion about Bear’s Ears.

Hughes’ affection for Trump wasn't all that surprising. Way back in college, Hughes wrote a column advocating for a wall between the U.S. and Mexico. Both men were land developers. Both loathe political correctness. And both seem to share the same cavalier attitude toward questions of conflict of interest.

Hughes even took a page from Trump’s playbook in September, tweaking Utah Gov. Gary Herbert over Twitter for rarely staking out a controversial stand. There was little love lost between the two Utahns. Last year, they clashed over what would have been the governor’s landmark piece of legislation: Medicaid expansion.

House Speaker Greg Hughes speaks about Healthy Utah while Gov. Gary Herbert looks on at the Capitol in Salt Lake City on March 12, 2015. | Deseret News Archives

Even though the governor’s Healthy Utah plan had the backing of the Senate and most of the Utah business community, Hughes and the House opposed it. It was the defining battle of the session, and if there was any question who wields more political power, that settled it. Insiders in the governor’s office say Herbert had hoped Hughes would be selected to the Trump administration — so he wouldn’t have to deal with him anymore.

“Greg has a personality and style that’s pretty unique for this state, which culturally can be passive-aggressive,” Hartley says. “He’s not that. He’s very direct and to the point, and he knows how to get things done. Does that mean he’s the most powerful politician in the state? That’s a tough one to answer.”

Two weeks later, Hughes opened the session with an address that seemed cribbed from a Trump stump speech. He announced that a "sophisticated crime enterprise" had taken advantage of the homeless situation in Utah and that drug cartels were “in our community.” He also used what was perhaps the most memorable line from Trump’s inaugural address, proclaiming the “carnage” in Salt Lake’s streets had to stop.

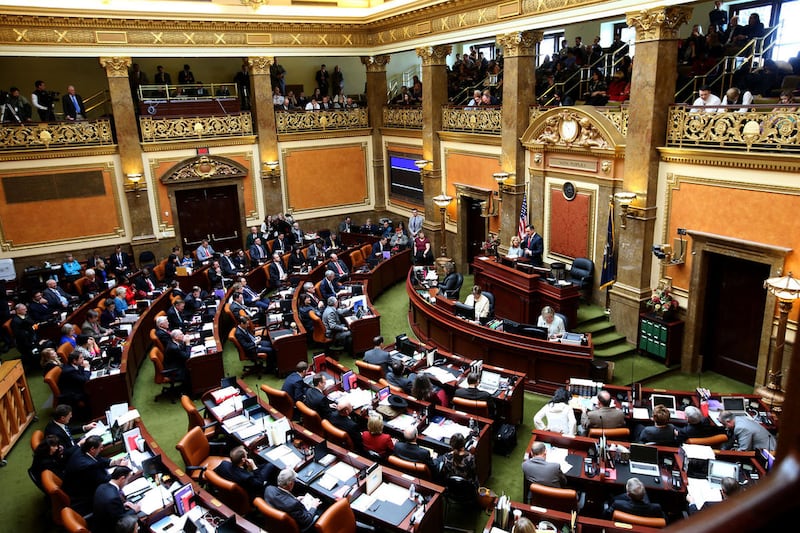

Speaker Greg Hughes addresses members of the Utah House of Representatives as they open their 2017 session on Jan. 23, 2017. | Scott G Winterton, Deseret News

Hughes had reason to feel confident. While the GOP has long controlled the state Legislature, it has rarely held power like it does now. With 63 of 75 House members belonging to the Republican Party, the Democrats have been reduced to nothing more than a hood ornament on a car they have no control over.

Most people thought the governor was at the wheel (according to a recent Utah Policy poll, nearly half of Utahns don't even know who Hughes is), but the speaker proved otherwise when he got his way on Medicaid expansion. What that means to the average Utahn is that anything they hope for this legislative session — a tax increase to fund schools, a bill on clean air, help for the homeless or changes in alcohol law — will have to go through Hughes.

But then, on the second day of the session, something happened no one saw coming, the sort of bombshell moment that can derail a rising political career. While Hughes was speaking from the dais, a text popped up on his phone: Something was going on a few miles away at the state courthouse.

There, a land developer and convicted fraudster named Marc Sessions Jenson was testifying in a hearing connected to the political corruption case against former Utah Attorney General John Swallow. Jenson said that on several occasions he met with Swallow and his predecessor, Mark Shurtleff, at a five-star resort in Newport Beach, California, to exchange cash for political favors.

Then Jenson dropped a stunner: Hughes had attended one of these meetings.

Hughes immediately took to Twitter to deny the allegations. A few hours later, he stood before a GOP caucus meeting to express outrage at the drama unfolding at the state courthouse.

“I want my colleagues to know I have never been to Pelican Hill,” Hughes said, microphone in hand, voice rising with indignation. “I've never attended a meeting with Mark Shurtleff. I don’t know this guy Marc Jenson. I wouldn’t know him if he was standing right here.”

One legislator wiped his brow with a napkin. Another looked down.

Throughout his political career, Hughes had been dogged by the whiff of scandal and corruption. He came to Utah in the early 1990s to help with Enid Greene’s U.S. congressional campaign, which ended with embezzlement charges against her husband that ruined her career.

Then, five years after his election to the Utah House, a legislator accused Hughes of offering her a bribe, for which he was issued an official reprimand for “unbecoming conduct."

Greg Hughes, Utah Transit Authority board chairman, sits in the driver's seat as the UTA demonstrates its first compressed natural gas bus in Salt Lake City on July 16, 2013. | Ravell Call, Deseret News

His tenure as chairman of the Utah Transit Authority was marred by allegations of fiscal mismanagement, inflated bonuses and sweetheart deals for another board member named Terry Diehl, who made about $24 million on a FrontRunner station in Draper — a deal that led the attorney general’s office to launch an investigation.

The Draper station was the subject of the Pelican Hill meeting, Jenson testified.

Hughes thought he had put all of this behind him. But this week’s sensational court testimony placed him back under the cloud of suspicion.

Before his fellow legislators, Hughes denounced the court proceedings Tuesday. A few gave him a standing ovation.

"I want them to keep my name out of their mouth on that circus of an event going on down there,” Hughes said, nearly yelling. “… I will, under oath, make sure I clear this.”

It’s too early to know whether Hughes is connected to Pelican Hill or has any links to the attorney general corruption scandal. Perhaps, like other allegations of ethical violations that have tainted his political career, these, too, will fizzle out. Either way, it's yet another twist in the story of one of the most colorful political figures in Utah history.

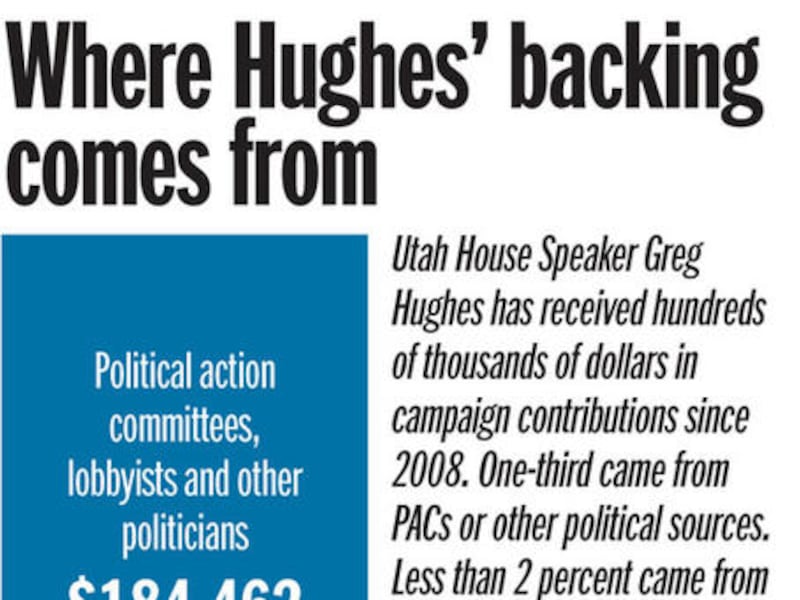

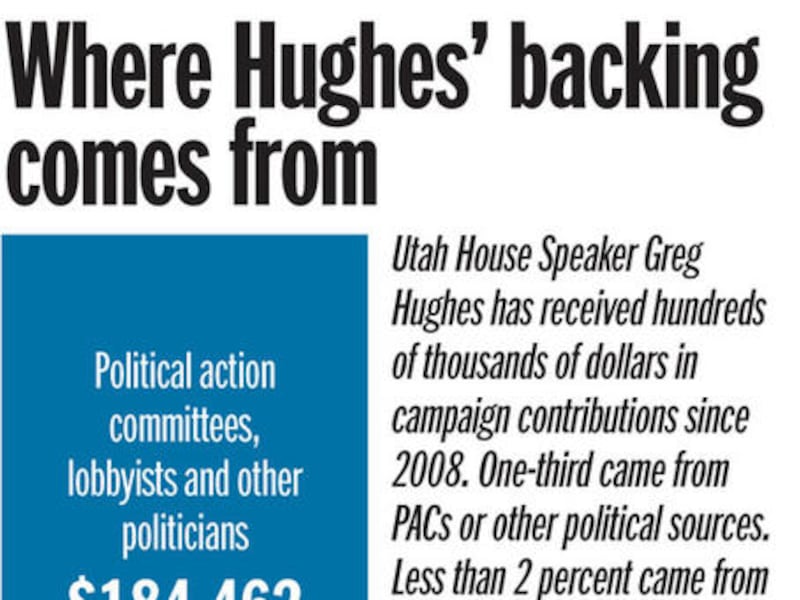

Web of influence

Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes is loved and hated by some of the most powerful people in the state. Here's a few.

Donald Trump Jr. Son of President Donald Trump. Hughes was one of Trump's most fervent supporters in Utah. He struck up a friendship with Trump Jr. and hosted a campaign fundraiser with him last fall.

Gov. Gary Herbert While Hughes says they agree on most major issues, he and Herbert have clashed publicly over Donald Trump, standardized testing, Medicaid expansion and the state prison move.

Jon Huntsman Jr. Hughes served as GOP party whip and head of the House Conservative Caucus during Huntsman's tenure as governor. The two developed a relationship of mutual respect, with Huntsman praising Hughes' coalition-building skills and Hughes later supporting Huntsman's presidential bid.

Scott Anderson President and CEO of Zion's Bank who has donated generously to Hughes' campaigns and vocally supported Hughes' legislation on education, homelessness and health care.

Joe Waldholtz Ex-husband of former Utah Rep. Enid Greene Mickelsen. Waldholtz and Hughes became friends while working on the Bush-Quayle campaign in Pittsburgh. Waldholtz later gave Hughes his start in politics by inviting him to work on Greene's campaign. It was later discovered that Waldholtz stole nearly $2 million to fund his wife's campaign, but Hughes remained loyal to his friend.

Rep. Brian King Utah House minority leader and Hughes' Democratic counterpart. King has challenged Hughes' stances on a variety of issues and has argued the way Hughes facilitated the Medicaid expansion vote "shows a Soviet-style subversion of democracy."

Terry Diehl Land developer and former UTA board member who, it later surfaced, made millions on a land deal near a Draper Frontrunner stop. Hughes defended him, saying there was no problem as long as Diehl disclosed his conflict of interest.

Sen. Howard Stephenson Republican state senator and frequent donor to Hughes' campaigns. Co-sponsored many bills with Hughes regarding education and property regulations. Co-hosted a radio show with Hughes called Red Meat Radio.

Beverly and James Sorenson Utahns who made billions founding Salt Lake City's Sorenson Companies and have been frequent donors to Hughes' campaigns. Upon James Sorenson's death in 2008, Hughes sponsored a resolution to honor him.Show AllCloseThe fighter

It was 1984, and Greg Hughes was pinned to the sidewalk outside an LDS church in Pittsburgh. He was 14 years old, a scrawny kid who fought all the time. His mom was an art student turned go-go dancer turned seller of cemetery plots who worked on commission, so sometimes she’d come home with an electric guitar for her son, and sometimes the power would suddenly flicker out.

He and his sisters moved all the time, and at each new school, the boys would test Hughes. When his mom found him smoking with other kids in the woods behind their house in seventh grade, she sent him to a summer school for troubled youths. He got in three fights the first day.

Now here he was again, in yet another fight. The family had joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when he was a toddler, and while that had brought stability to the home, it hadn’t ended the chaos that seemed to swirl around Hughes.

The kid on top of him was much bigger, and in that moment Hughes realized he couldn’t win the fight. But he could make it end. And that was when he spit the blood in his mouth in the kid’s face.

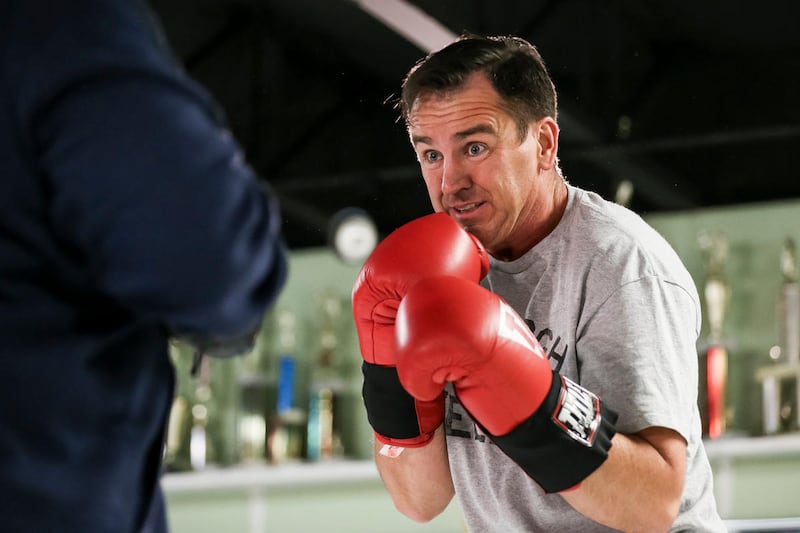

Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes trains with his boxing coach, Eddie "Flash" Newman, at Flash Academy in Holladay, Utah, on Jan. 13, 2017. | Spenser Heaps, Deseret News

“When you’re raised by a single mom, you don’t know how to be a man,” Hughes said. “You don’t know what that means. You’re kind of winging it. And you’re looking for ways to prove that you are a man.”

Hughes took pains to cover up his family’s poverty. He qualified for free lunch, but he’d sooner go hungry rather than pull out the yellow-colored ticket in the cafeteria line. Embarrassed that he didn’t have clothes for gym, he skipped class.

By high school, Hughes was living with a family friend in Wexford, a nicer part of town where he stood out even more. His mother scoured Goodwill for the Ralph Lauren shirts that his classmates wore, and Hughes saved his tip money from his job as a bellhop at the Sheraton to buy more.

He was deeply affected by "The Outsiders," a novel that came out in 1967 that tells the story of two rival groups divided by social class, the Greasers and the Socs (short for Socials). Hughes identified with the Greasers. He hated Socs.

"I didn't like being poor,” Hughes said. “I didn't like how my peers my age looked at people who they thought were poor. And I didn't want to fall into those categories — into any category, really."

In the summer of 1988, while looking for a way to kill time before he left on his LDS mission, Hughes was offered a job as a scheduling assistant for the Bush-Quayle presidential campaign through a chance family connection. By day, Hughes accompanied the Bushes and Quayles on goodwill tours of local hospitals, charities and businesses. By night, he would stay up late in the campaign offices browsing position papers.

"I learned that there were positions that I didn't know were positions on issues," Hughes said. "I'd compare and contrast how I saw the world with what I was reading … I started listening to the debates, the campaign itself, what Herbert Walker Bush was campaigning on. I started to identify with that. And I started to like it."

It was also during that time Hughes would meet someone who would give him his own start in politics years later. It’s an association that would later come to haunt him.

Political rise

When Hughes got back from his LDS mission in Papua New Guinea in 1991, he moved back to Pittsburgh, planning to work on the Bush re-election campaign. Then he went to a Young Republicans event in Utah and heard a rising star named Enid Greene.

“I was ready to go 'Braveheart' right there listening to her,” Hughes told the Salt Lake Tribune in 2015. “I just made the decision right there, I’m not going back to Pittsburgh. I wanted to help Enid.”

Greene (now Enid Greene Mickelson) was the head of the National Young Republicans. She was dating Hughes’ friend, a fellow Pittsburgh native named Joe Waldholtz. Hughes moved in to Greene’s basement in Federal Heights to work on her 1992 congressional campaign, which she ended up losing.

Around the same time, Hughes enrolled at what was then-Utah Valley State College, where he wrote a column for the school paper called The World According to Greg. The columns were filled with a strain of populist conservatism now familiar to anyone who voted for Trump. He railed against then-President Bill Clinton’s policies on national debt and Somalia, bemoaned the growing chorus of "politically correct whiners,” and, most presciently, advocated for a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Congresswoman Enid Waldholtz, R-Utah, and her husband, Joe, arrive at their voting place in Salt Lake City on Nov. 8, 1994. Nov. 8, 1994. | Steve Wilson, Associated Press

When Greene ran again in 1994, this time successfully, Hughes once again helped on her campaign with Waldholtz, who was now married to Greene. As part of the first Republican House majority in 40 years, Greene quickly made a name for herself with then-Speaker Newt Gingrich, securing a spot on the House Rules Committee, the first time in 70 years a freshman had done so.

But her rising star quickly flamed out when it was discovered Waldholtz had embezzled nearly $2 million from Greene’s father to fund her campaign.

In December 1995, she hosted a marathon press conference in Washington, D.C., in which she offered a teary apology. When a reporter kept pushing Greene on a particular point, Hughes stood up from the back and yelled at the reporter to knock it off.

“Greg is very loyal,” a well-connected political operative in the state said. “Loyalty has a wonderful attribute to it, and it can be a knife to you. He’s loyal to people who have done things that are not in their best interest, and that reflects on Greg.”

Hughes said then that he had nothing to do with the scandal involving Waldholtz, who is now in jail serving a 15-year sentence.

“Does my loyalty sometimes get me in trouble?” Hughes says. “Yeah.”

But ask Hughes what trait he most admires in men and he’ll answer: loyalty.

Women? Loyalty

His defining characteristic? Loyalty

Trait he most deplores in others? Disloyalty

Way he’d like to die: In battle

“Loyalty is a great quality if you’re a priest,” Hughes’ friend says. “It’s not a great quality when your friends and allies do things and the finger points at you.”

Slugging to the top

After Greene’s fall from grace, Hughes re-emerged in Utah politics, showing up to help with low-level political campaigns, like the 1999 Provo City Council race of Stan Lockhart, the future Utah Republican state party chairman and husband to the late House Speaker Becky Lockhart. He also started building what would eventually become a sizeable number of apartment buildings along the Wasatch Front.

A few years later, Hughes ran and won election to the House as a representative of Draper. Hughes quickly earned a reputation as someone with a talent for negotiations and dealmaking, reinforced by a brash, sometimes intimidating style.

“The joke about Greg is that when he became whip to the speaker he took the whip part literally,” another political insider says.

Rumors started circulating he could go too far. In 2008 a former legislator named Susan Lawrence filed an ethics complaint alleging Hughes had tried to bribe her with $50,000 in campaign contributions to change her vote on a controversial school vouchers bill.

Hughes denied the charges, saying Lawrence misrepresented him. Sheryl Allen, a former legislator who testified against Hughes, says Lawrence has always stood by her version of events.

The case went before a board of House lawmakers — four Republicans, four Democrats — who cleared Hughes after a week of closed-door testimony. However, the members signed a letter calling Hughes’ conduct “unbecoming” and requested he “take steps to change his behavior.”

From left to right, Gov. Jon Huntsman, Sen. John Valentine, Rep. Greg Hughes and Sen. Scott Jenkins unveil proposed alcohol policy for Utah during a press conference at the Capitol in Salt Lake City on March 9, 2009. | Kristin Murphy, Deseret News

In 2009, hungry to regain his credibility, Hughes signed on to one of the riskiest fights of his political career with then-Gov. Jon Hunstman Jr., who had decided he wanted to modernize Utah’s liquor laws. He asked Hughes for help.

“He was a coalition builder,” Huntsman said. “He was a doer. His word was his bond, which I prized highly. And he was willing to take on things that were relatively controversial.”

Huntsman wanted to eliminate the part of the law that required bar patrons to sign up as members of a “private club” to order a drink, which he thought was driving away tourists.

But the opposition was formidable. A large chunk of Utahns didn’t want the liquor laws touched. The Utah chapter of Mothers Against Drunk Driving thought the changes would increase the number of DUIs. And the biggest stakeholder of all, the LDS Church, was reluctant to loosen the four-decade old law.

“I was told in no uncertain terms when I started my journey as governor: That one thing you want to do? Don’t even try,” Huntsman said.

Hughes’ strategy was to show that the private club law did little to stop underage drinking. The advent of ID scanners, he proposed, would allow the state to do away with private club designations and do more to combat underage drinking than membership fees. The issue, he argued, was not only about the economy but also public safety.

By the end of the session, the Hughes bill passed, and Huntsman got the most sweeping reform to Utah’s liquor laws in four decades.

The shadow of suspicion

At the same time, questions about ethics continued to trail Hughes.

In 2006, he became the first sitting lawmaker to be appointed to the board of the Utah Transit Authority. This caught the attention of political gadfly Claire Geddes, who began circulating a petition arguing that Hughes’ position in the Legislature, and his landholdings throughout the Wasatch Front, could pose a conflict of interest.

Greg Hughes, Utah Transit Authority board chairman, speaks to members of the media about the first compressed natural gas bus in Salt Lake City on July 16, 2013. | Ravell Call, Deseret News

Geddes gathered 200 signatures, but she said no one cared. “I took it to editorial boards, and everyone just put it aside," Geddes said. "The UTA would come in and do their dog-and-pony show and everyone just said, ‘Oh, they’re doing a bang-up job.’”

But Geddes, the founder of Utah Legislative Watch, remained troubled by the possible links between Hughes and developer Terry Diehl, who also sat on the UTA board.

While Hughes and Diehl were on the board, Diehl sold the development rights to land near what is now the Draper FrontRunner station to another developer named Jeff Vitek. According to documents released in 2011, Diehl made around $24 million on the deal.

Hughes raised eyebrows for his fierce defense of Diehl.

Asked by a lawmaker why he hadn’t inquired into how much Diehl had made off of the transaction, he replied, “As the chair of the board I'm not privy to any of that. It's not a board matter.”

Four years later, a scathing audit blasted UTA for what auditors said was a pattern of waste, excess and sweetheart deals to developers like Vitek, who was pre-paid $10 million for a parking garage he never built. By the time the report was published, most of the money had been returned, but UTA was still owed about $1.7 million, according to auditors.

Mark Shurtleff, Utah’s attorney general at the time, said he put two investigators on the case and they gathered hundreds of pages of evidence. In 2012 he passed their work on to the FBI.

That inquiry is still open with the FBI, according to a source with knowledge of the investigation.

"To me, it never passed the smell test, but we could not see evidence of a crime," Shurtleff said. "If there had been (a crime), their tracks had been covered enough."

Attorney Thomas Karrenberg, left, sits with his client, Rep. Greg Hughes, while the public leaves during a formal ethics investigation of Hughes at the Capitol on Oct. 8, 2008. | Laura Seitz, Deseret News

David Irvine, an attorney for the Democratic lawmakers who accused Hughes of ethics violations in 2008, said weak ethics laws in Utah allow politicians to skirt around conflict-of-interest issues.

Hughes "is not reluctant to get chalk on his shoes in determining where the limits are," said Irvine. "That's not to say that he's the only one or he is the most flagrant tester of the rules. … There are probably about twelve to fifteen people in the Legislature who are more than willing to get chalk on their shoes as they see precisely where the boundary line might be.”

In 2012, shortly after resigning from the UTA board, Diehl filed for bankruptcy for $41 million in debt — including $500,000 to the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. Diehl and Hughes remain friends and business partners. Diehl said they have several subdivisions they're working on together, and Hughes says Diehl often finds him land to develop. If the project is successful, he pays him a finder's fee.

"Terry is a character," Hughes says. "I always joke that if a Vegas mobster and a showgirl had a baby, and a stork picked it up and dropped it in the living room of a good Mormon family in Cottonwood Heights, that baby would be Terry Diehl."

Hughes acknowledges that his association with Diehl raises eyebrows about the way he may have used his influence as a lawmaker or UTA chairman on land deals. But he insists there's nothing shady going on and that they've both followed the required disclosure laws.

"The guy’s not been arrested, he’s not got a criminal record, it’s not like I’m hanging out with known criminals," Hughes says. "Characters, yes. But not criminals."

For his part, Diehl says "there's no question" he profited from the Draper land deal, but that no laws were broken and no one else on the board made any money on the transaction.

“Let’s be really clear about these allegations that (Hughes) is unethical,” says a longtime political lobbyist who has raised money for state and national Republican campaigns. “He has enough people who don’t like him that if he was unethical he’d be in jail by now. It’s dishonest and unfair for people to keep saying that. He’s been under a microscope for so many years and had people take swings at him. If he was really unethical he wouldn’t be speaker, he wouldn’t be in the Legislature.”

The speaker vs. the governor

Hughes was elected speaker of the House in 2014, riding the wave of an election cycle that produced the largest Republican majority in the House since 1967.

The natural tension between the governor, who proposes a budget, and the Legislature, which actually decides the budget, emerged almost immediately. But it wasn't until Medicaid expansion that Herbert and Hughes' differences in personality and style spilled into public view.

“The governor had the support of the media and all the big business guys who go to the Alta Club and the symphony and stuff like that,” says one well-connected lobbyist who has raised money for local and national Republican leaders. “But Hughes wouldn’t bend. And it died.”

In Hughes’ office, alongside his Make America Great Again hat and his Ann Coulter talking doll, he’s framed a memento of that battle.

It’s a cartoon, drawn by the Salt Lake Tribune’s Pat Bagley. It depicts Hughes as a gangster, complete with a pinstripe zoot suit and a Tommy gun smoking at the barrel, bullet casings scattered on the ground.

Lying before Hughes in a pool of blood is a doctor labeled Healthy Utah — the governor’s Medicaid expansion plan.

Off to the side the governor and the Senate president look aghast, two wet noodles powerless to stop what has just happened.

"My son looks at that and goes, 'Dad, why do you hate doctors?'" Hughes says. "I'm like, 'Son, I don't hate doctors.'"

So why is it on his wall?

Hughes grins.

“Because I’m proud of it,” he says.

While the division of power in Utah has been split between the governor and the speaker of the House for at least a decade, it’s never been more pronounced than it is now, partly because of the personalities of Herbert and Hughes. While Hughes says the battle over Medicaid expansion "took a toll" on their relationship, tensions have only risen since then.

In March, as Herbert was heading into the primaries against challenger Jonathan Johnson, he floated the idea of calling a special session to eliminate SAGE testing, a statewide proficiency exam for students in the third grade through high school.

Hughes hit back: "The legislative branch has not been grafted into the governor's re-election campaign," he said in a statement. "We do not take on a weighty issue like this without public hearings and necessary deliberation."

Herbert backed off of the proposal the next day.

In September, they clashed again, after Herbert stepped into a debate about allowing high school coaches to recruit athletes regardless of where they live.

"Profile in courage. Courageous stand on high school sports. Do you have an opinion about who should be President of US?" Hughes tweeted.

Greg Hartley, Hughes’ chief of staff, called those statements a "last resort thing, when talking doesn't work."

Asked whether he thinks Herbert focuses on the wrong issues, Hughes demurred.

"You'd have to ask him what he's focusing on," Hughes said. "I'm not exactly sure."

Asked whether he thinks the governor is a weak leader, he laughed. It was a few days before the session.

“I can’t go on the record with things like that,” he said.

When asked for comment on this story, the governor released this statement: "Speaker Hughes is a passionate, hard-driving advocate. While we have at times disagreed on policy or process, I enjoy working with him on areas of mutual concern that benefit the state."

At times, Hughes can seem like a smaller version of Trump — confrontational, brazen, beset by scandal wherever he goes. In this latest incident, which could amount to nothing by the time the session is over, there are also parallels. Just days into the session, Hughes was taking to Twitter to defend himself against Jenson, intimating to colleagues that he’s the victim of a witch hunt.

Minutes after Jenson’s testimony, Shurtleff joined Hughes on Twitter, dismissing Jenson as a liar. Later, Hughes’ chief of staff tweeted that he could prove Hughes wasn’t at the Pelican Hill meeting. Hughes says his lawyer is gathering documentation that will prove he wasn't there.

How these allegations will impact Hughes’ relationship with the governor or his ability to lead the House is an open question. A member of the governor's staff said he doesn't think Jenson's testimony will hurt the speaker, at least not for now.

Rep. Greg Hughes, center, walks with his wife, Krista, and attorney Thomas Karrenberg through the state Capitol on their way to address the media after Hughes was exonerated by an ethics committee in Salt Lake City on Oct. 17, 2008. | Deseret News Archives

"He beat back an ethics complaint eight years ago, and his profile actually raised because of it. Just because there's smoke doesn't mean you're going to get burned. The speaker is as powerful now as he was two days before the session started."

Hughes said these sorts of incidents are a "pattern" in his life and he can't quite figure out why. He attracts trouble, even at BYU football games, where he's one of the few fans who gets into fights with University of Utah fans.

"It’s been that way from youth, to … well, I don’t know,” Hughes said. “I don’t know why the tapestry of my life requires me to go through stuff like this. I will tell you this. I was born for the storm. When things are calm and things are easy I get lazy, I slow down, I’m not as aggressive or focused. For some reason, maybe the man upstairs wants me on my toes."

"I don't know why my life draws these conflicts," he continued. "Or why it keeps happening."

The fight ahead

It’s a warm Friday afternoon in Holladay, and inside a stuffy boxing gym lined with posters of Oscar De La Hoya and Floyd Mayweather, Hughes is working the heavy bag.

Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes, R-Draper, trains with his boxing coach, Eddie "Flash" Newman, at Flash Academy in Holladay, Utah, on Jan. 13, 2017. | Spenser Heaps, Deseret News

He’s wearing a sweat-soaked Pittsburgh Steelers T-shirt, and beneath his gloves his hands are wrapped in Steelers yellow. It’s the sort of place you might have expected Hughes to end up had you met him in Pittsburgh 40 years ago.

Hughes leans on the ropes to catch his breath. His trainer, Eddie “Flash” Newman holds out a deck of cards. He tells Hughes to cut the deck and has him pull three cards: one for pushups, one for situps and one for squats. Hughes pulls all face cards. He cusses under his breath.

“You’re going to make me do this in front of them?” he asks, looking at the two reporters and a photographer outside the ring.

Hughes usually looks like he’s in control of any setting — whether it’s the Legislature, his office or in battles with the governor. But for once, he looks tired, unsteady, even vulnerable.

When Hughes finishes his exercises, he ducks under the ropes and sits down on a bench, sweat dripping from his nose.

Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes takes a breather while training with his boxing coach on Friday, Jan. 13, 2017. | Spenser Heaps, Deseret News

“Any other questions?” he asks the two reporters. He has the look of someone subjecting himself to interrogation. “Any more of 'This is Your Life?’”

Favorite music? Hip hop.

Political figure he most admires? JFK.

The worst experience of his life? Other than the death of his mother, the ethics investigation in 2008.

"That situation hurt my family," said Hughes, who is married with three children. "My daughter’s 17 now, but she was a little girl when those things (came out) and they’re saying it on the news, they’re saying it everywhere, and I walked up to my daughter’s room one night and she was crying because of what they were saying about her dad. And it still upsets me."

Rep. Greg Hughes holds his sleeping daughter, Sophie, during a joint session of the Legislature in Salt Lake City on Jan. 15, 2007. | Deseret News Archives

He pauses to control his voice.

"When you’re outside the ropes of politics and policy, and you hurt people’s families …."

He doesn’t finish the sentence.

"Anyway, that’s what makes me miserable, is when people are hurt that have no business to be hurt," he said.

The timer beeps three times, a loud and insistent squawk. It’s time to get back in the ring. Hughes turns back to Newman. They get on like old college roommates, cussing at each other, levying playful insults. Newman calls Hughes a “big baby.” Hughes puts his gloves up.

The timer goes off again: Beep. Beep. Beep.

Then silence.

Hughes does what he’s done his whole life: He pulls back and swings.

Contributing: Lauren Fields, Mariana Chrisney

Correction: A profile of Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes that appeared in Sunday's paper incorrectly stated that Hughes met with representatives of the Utah Transit Authority and a freshman lawmaker about two weeks before the session. He met with representatives of the Utah Department of Transportation and the lawmaker was a sophomore. The article also misstated how many Republicans are in the House. There are 62, not 63.