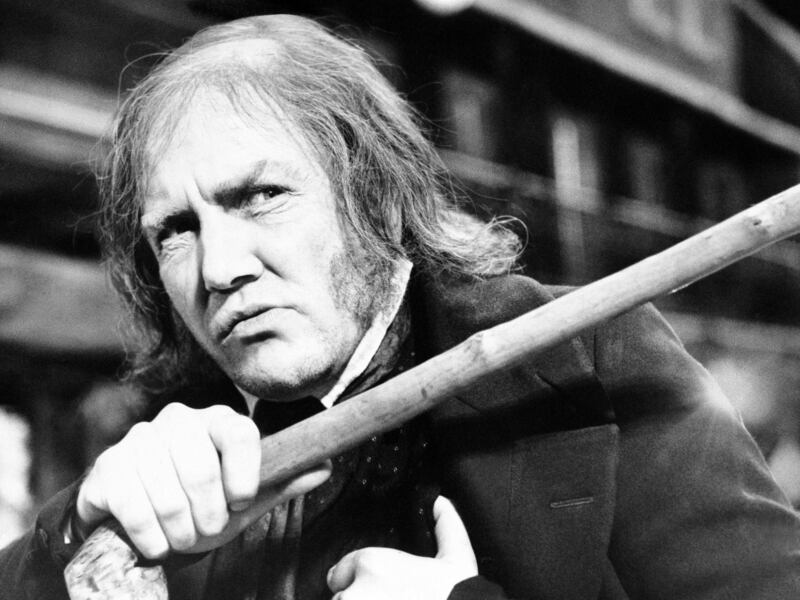

When Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” opens, Ebeneezer Scrooge appears as an unflinchingly self-assured, rich, productive and efficient bastion of success. But within a night, this same man, awakened to the reality of the empty, lonely, isolated, bitter life he has chosen is trembling in fear, sobbing violently to the Ghost of Christmas future, “Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of things that May be, only?” We pity Scrooge in his hopeless, empty, lonely, isolated state. And yet, in many ways, Scrooge reveals what we ourselves are grappling with in our current culture.

Columnist Nathanael Blake recently described it well. “Despite unprecedented wealth, knowledge, entertainment options and technology that increasingly allows us to reside within curated personal realities, our culture creates little of enduring worth and is suffused with boredom and loneliness.”

If, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention argues, “life expectancy” gives us a snapshot of the nation’s overall health, loneliness and emptiness seems to be the plague of our day. In the past three years for which data is available, we have continued to see a drop in average life expectancy due to a continued increase in the tragedy of preventable deaths — drug overdose and suicide.

Rates of major depression among young adults rose 63% between 2009 and 2017, and dramatically increasing rates among adolescence have been a cause for public alarm. Loneliness has been identified as the modern-day epidemic with 35% of Americans over 45 say they are chronically lonely.

At the same time, the fertility rate in America continues to steadily decline, now well below the replacement rate. Blake surveyed the many reasons often offered for such a decline — “environmental concerns, debt, the cost of raising children” — but concludes “the truth is that our culture is ambivalent about whether life is worth passing on.”

Christmas is, if anything, the great reminder of hope.

In a lecture at BYU, New York Times columnist David Brooks recently described his own awakening to the tragic “logical end” of our cultural meritocracy — a world, not unlike Scrooge’s that idolizes reputation, time, productivity and achievement — ultimately leading to “a lot of people who are very lonely, very isolated and very afraid.”

T.S. Elliott knew such would be the case, once saying, “the end of a purely materialistic civilization with all its technical achievements and its mass amusement is ... simply boredom. A people without religion will in the end find that it has nothing to live for.”

Awakened to the profound hopelessness and loneliness of his life, Scrooge pled to the Spirit, “Your nature intercedes for me, and pities me. Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me, by an altered life.” For Scrooge, and for us, that altered life will come in turning toward one another, in creating a culture where, as Brooks described, we are “seeing each other deeply and being deeply seen … when you forget where you end and something else begins, when you really are seeing deeply into each other.”

When daylight enters his room and he realizes that he yet lives, Scrooge grabs his bed-curtains exclaiming, “They are not torn down. They are not torn down, rings and all. They are here — I am here — the shadows of the things that would have been, may be dispelled. They will be. I know they will.”

Christmas is, if anything, the great reminder of hope. In the darkest part of the year, it represents the brilliant light of a second chance — and not just a second, but as many chances as we will humbly receive to grow, to choose differently, to become better.

Jenet Jacob Erickson is an affiliated scholar of the Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University.