SALT LAKE CITY — By now, it’s an image most of us have seen over and over, whether on our social media feeds or with our own eyes: a bare grocery store shelf, where toilet paper, food or water was plentifully stocked just weeks ago. For many, it’s an image that seems ominous, indicating that there is scarcity in a time of national crisis.

The problem is especially bad in Utah, which is leading the nation in year-over-year sales at local grocery stores, according to revenue patterns analyzed by Womply, a software firm with offices in Lehi.

“These numbers suggest that Utahns are ransacking grocers and supermarkets at a rate that isn’t seen anywhere else in the country right now,” wrote Brad Plothow, vice president of corporate marketing and communications at Womply, in a statement.

But is the country actually in danger of running out of essentials like food, toilet paper and surgical face masks? And after a Wednesday earthquake frayed nerves across the Wasatch Front, what can residents expect?

While the supply chain for certain products is certainly under stress, with manufacturers struggling to keep up with demand, people’s fear-based buying habits may be exacerbating the problem, said Paul Sheard, senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

“It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy,” said Sheard. “If people are concerned that the shelves will become empty, they will become empty.”

No toilet paper on the shelf

Some people may be stocking up on supplies because they fear that disruptions in trade with China or other countries could produce shortages in the United States — a phenomenon creating problems with the global supply of face masks.

While hospitals and governments hunt for surgical masks to protect doctors and nurses who are responding to the pandemic, China — which made half the world’s masks before the coronavirus emerged there — has claimed mask factory output for itself and has only just started to share with other countries, The New York Times reported. This problem is only made worse by the unnecessary buying of face masks by healthy individuals, rather than saving them for doctors, nurses or immunocompromised people.

But toilet paper is a different story. North America imports only 10% of toilet paper from China and India, according to David Wessel, director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution.

“There is plenty of toilet paper in the U.S., but when a lot of people start buying and hoarding it, then other people — not completely irrationally — say that if they’re going to hoard it, I better get extra, too. That’s classic panic buying,” Wessel wrote in an email to the Deseret News.

But the market economy is designed to quickly adjust to disruptions like this, said Sheard.

“If there’s no toilet paper on the shelf, then guess what?” he said. “Toilet paper manufacturers have a huge incentive to get that toilet paper onto the shelf as quickly as possible.”

Indeed, the spectacular demand for toilet paper is exerting pressure on the supply chain, said Holly Wade, research director at the National Federation of Independent Business.

“There’s a disconnect between supply and demand,” said Wade. “They are having to increase manufacturing capacity and it is difficult to do that in such a short time frame. But it is happening and those gears are turning to get the products out to market as soon as possible.”

This is especially challenging in regards to toilet paper. Because it is such a large product, stockpiling large amounts of inventory is not profitable, so suppliers are struggling to catch up, The New York Times reported. Right now, that means that some businesses are out of stock for hours, or even a day or two, before they get a new shipment.

But this gap between demand and supply is fundamentally a result of human psychology, said James Watson, a senior economist at Oxford Economics. In other words, if people stop panic-buying and only bought as much toilet paper as they actually need (a two-week supply, in case of illness or quarantine), then the pressure on the toilet paper supply chain will ease.

“At the moment, the fear of the virus is having more of an economic impact than the virus itself,” said Watson.

Will people have to go without food?

In addition to empty shelves, many grocery stores across the country are experiencing another phenomenon as a result of increased demand: long lines snaking all the way out the door and into the street.

While for some these long lines might spur fears of food shortages, the largest meat producers and dairy farmers in the country have stated that the food supply chain remains healthy and that they have been working overtime to keep up with skyrocketing demand for food, The New York Times reported.

“There is food being produced. There is food in warehouses,” Julie Anna Potts, chief executive of the North American Meat Institute, a trade group for beef, pork and turkey packers and producers, told The New York Times. “There is plenty of food in the country.”

Over the past month, canned meat sales went up by more than 40%, sales of rice jumped by more than 50%, and Kroger stated that demand had increased by 30% across all categories, the Times reported, and orders for hot dogs at Walmart and Costco increased by 300%.

Some grocery store chains — such as Walmart and Stop & Shop — are scaling back on their hours to make time for sanitizing, to help workers stay healthy and to give employees time to restock shelves, the Times reported.

As with toilet paper, the issue isn’t so much whether enough of the product exists or will run out completely, but the pressure put on the supply chain by panic-buying: having so much unexpected demand all at once, making it difficult for producers to catch up, said Wessel with the Brookings Institution.

For example, some items can’t move any faster than nature allows, such as the fact that it takes 60 days to get a chicken to a customer, from incubation to hatching to the maturation process of the bird, Matthew Wadiak, who runs Cooks Venture, a chicken supplier based in Arkansas and Oklahoma, told the Times.

“Should people expect goods to truly run out?” said Wesell “There may be some temporary shortages, but as the truckers are on the road, the farms are working and the food processing plants remain open while the rest of us are told to work at home, I think they will be temporary.”

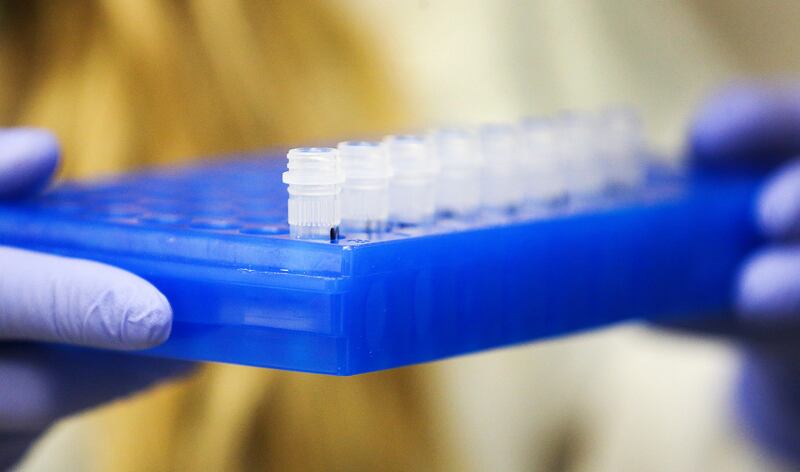

Why aren’t there enough coronavirus test kits?

If uncertainty fuels panic-buying and panic-buying fuels supply chain issues, then one way to soothe American’s fears would be for the government to give people more information — especially accurate numbers of confirmed cases in each state, said Baruch Fischhoff, a professor of public policy at Carnegie Mellon University.

But that would require widespread testing — an effort that itself is being hamstrung by a supply chain issue. As of March 8, the U.S. had the lowest rate of coronavirus testing per capita of any developed country.

Before a laboratory can perform a coronavirus test, it must first extract RNA from the virus samples taken from a patient. This extraction requires a separate kit, and the raw materials required for that kit are running low, Business Insider reported. Qiagen, a Netherlands-based company that makes the RNA-extracting kits, told Politico its supplies are back-ordered.

”This is a period of extraordinary demand for the coronavirus testing workflows, some of which include Qiagen products,” a spokesman for Qiagen told Business Insider last week. “And yes it is true, that this demand is challenging our capacity to supply certain RNA extraction kits used for SARS-CoV-2 related LDTs.”

The company is increasing production at its manufacturing sites in Hilden, Germany, and Barcelona, Spain, but it’s unclear how long it will be until enough kits are produced to meet the testing demand in the United States.

A Utah-based diagnostic testing company called Co-Diagnostics said Tuesday that it is seeking approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a COVID-19 test that is already being used in Europe, and that it has resources to produce 50,000 or more of the tests each day from its facility in Salt Lake City.

“With FDA approval through emergency use authorization, we could supply all of the testing needs in Utah and around us easily,” Co-Diagnostics communication direct Seth Egan told the Deseret News. “We sit here a little bit amazed that we have a test available in European nations but we can’t sell it as a clinical diagnostic in our own home state. We do have the ability to make 50,000-plus tests a day and get them out to our community.”